Solastalgia: When Home No Longer Feels Like Home

The profound emotional distress caused by environmental changes to one's home environment is becoming a recognized psychological phenomenon. As our planet transforms due to climate change, urban development, and natural disasters, many people experience a deep sense of disconnection from once-familiar surroundings. This growing condition, termed "solastalgia," represents the homesickness one feels while still at home. The concept helps explain why environmental degradation impacts not just our physical health but our mental wellbeing and sense of identity. Read below to understand this emerging phenomenon and its implications for communities worldwide.

The Birth of a New Concept

Solastalgia was first coined by Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht in the early 2000s while studying the psychological impacts of large-scale coal mining on communities in New South Wales. The term combines the Latin word “solacium” (comfort) with the Greek root “algia” (pain) to describe the specific form of distress caused by environmental change. Unlike nostalgia, which involves longing for a place you’ve left behind, solastalgia occurs when people remain in their changed environment but experience grief over its transformation. Albrecht documented how residents near mining operations reported feelings of powerlessness, depression, and loss of place-identity as their familiar landscapes were dramatically altered.

The concept quickly resonated with researchers studying communities affected by natural disasters, climate change, and industrial development. Psychologists noted that people’s emotional connections to their environments run deeper than previously acknowledged in mental health frameworks. When familiar landscapes change drastically—whether through deforestation, rising sea levels, or urban development—the psychological impact can be profound and long-lasting. This place-based distress represents more than simple sadness; it constitutes a legitimate form of grief that challenges our understanding of environmental psychology.

Beyond Individual Experience: The Social Dimensions

Solastalgia manifests differently across communities and cultures, particularly affecting those with strong traditions of connection to land. Indigenous communities worldwide have articulated these feelings for generations, as their ancestral territories face mining, logging, and climate impacts. For many indigenous peoples, land isn’t merely property but an extension of cultural identity and spiritual practice. When these environments change irrevocably, the loss extends beyond physical resources to encompass cultural heritage and community wellbeing.

Rural farming communities also experience distinct forms of solastalgia as agricultural patterns shift due to changing climate conditions. Farmers who have worked the same land for generations describe profound disorientation when familiar seasonal patterns become unpredictable. In Australia’s drought-stricken regions, researchers documented increased depression and anxiety among farmers watching their once-productive lands transform into dust. Similarly, coastal communities facing rising sea levels and increased storm activity report feeling betrayed by environments that once provided sustenance and security.

Urban residents aren’t immune either. Rapid gentrification and development can trigger solastalgia when familiar neighborhoods transform beyond recognition. Longtime residents often describe feeling like strangers in their own communities as beloved local establishments disappear, architectural character changes, and social networks dissolve. The psychological impact of such changes disproportionately affects elderly residents and those with limited mobility, who may have fewer opportunities to build new place attachments elsewhere.

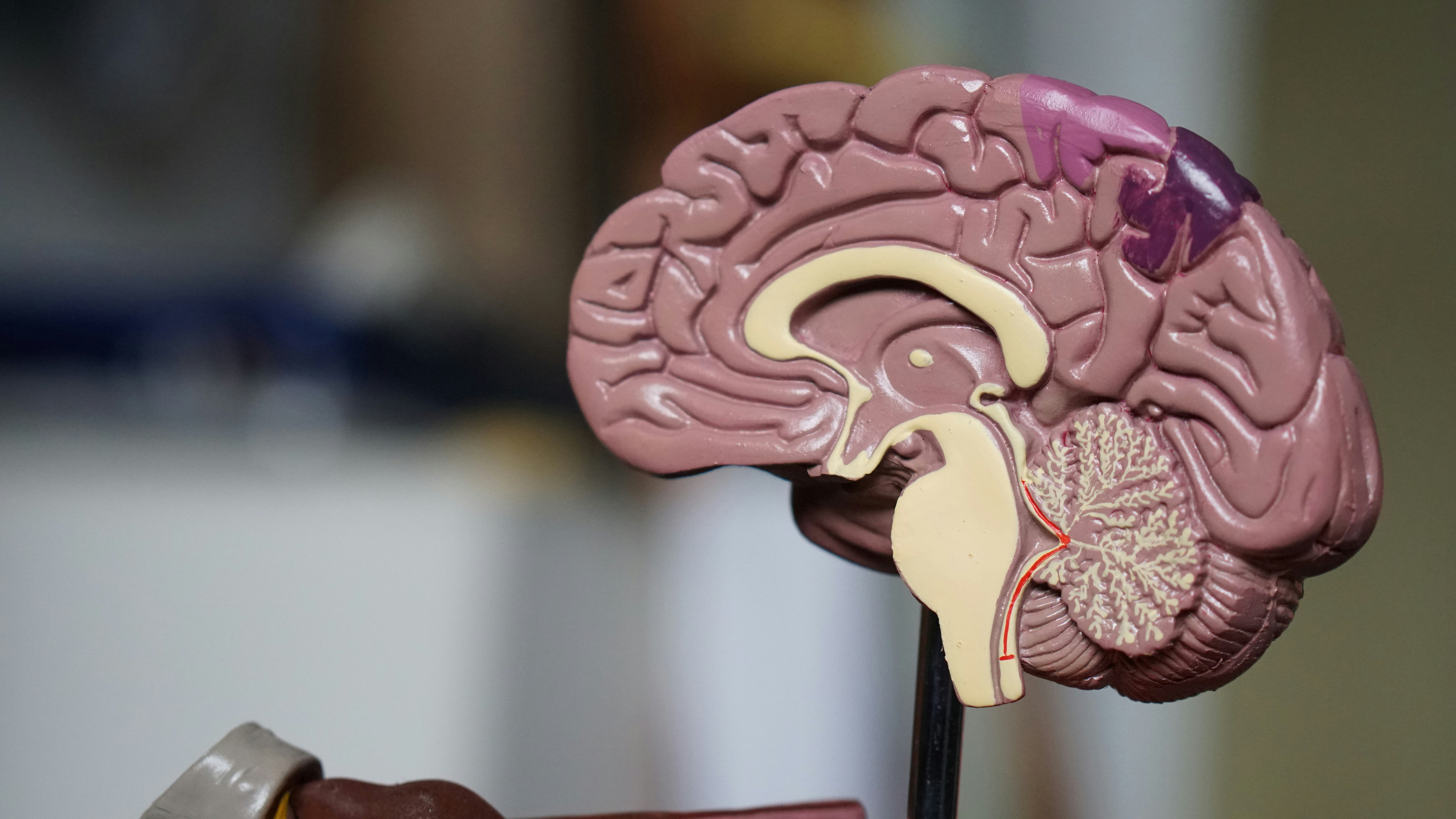

The Neurological Basis of Place Attachment

Emerging neuroscience research helps explain why environmental changes trigger such profound emotional responses. Our brains form intricate cognitive maps of familiar environments, with the hippocampus playing a central role in spatial memory and navigation. These mental maps become interwoven with our autobiographical memories, creating a neurological foundation for place identity. When physical environments change dramatically, our internal maps no longer match external reality, creating cognitive dissonance and emotional distress.

Brain imaging studies reveal that viewing familiar places activates regions associated with self-concept and emotional regulation. This suggests that our environments become neurologically integrated with our sense of self. The brain’s threat detection systems also engage when familiar environments change unexpectedly, triggering stress responses similar to those experienced during other forms of loss. This neurological perspective helps explain why environmental changes can feel so personally threatening, even when individuals aren’t directly endangered by them.

Researchers have observed that place attachment involves multiple sensory modalities—not just visual recognition of landmarks, but familiar sounds, smells, textures, and even the quality of light in different seasons. When these sensory experiences change or disappear, the full sensory framework supporting our place attachment becomes disrupted. This multisensory disruption helps explain why even seemingly minor environmental changes can trigger profound emotional responses in affected individuals.

Clinical Recognition and Therapeutic Approaches

Mental health professionals increasingly recognize environment-related distress as a legitimate clinical concern. While solastalgia isn’t formally classified in diagnostic manuals, therapists report growing numbers of patients expressing grief, anxiety, and depression related to environmental changes. Some clinicians have begun developing specialized approaches to address these concerns, drawing from existing frameworks for grief counseling while acknowledging the unique aspects of environment-related loss.

Ecotherapy represents one promising approach, incorporating natural environments into therapeutic practice. By helping clients rebuild connections with remaining natural spaces, ecotherapists aim to restore a sense of environmental belonging. Community-based interventions also show promise, particularly those that engage affected populations in environmental restoration projects. Such collective action can transform passive grief into active hope, providing both ecological benefits and psychological healing.

Some therapists emphasize the importance of ritual and ceremony in processing environmental grief. Drawing inspiration from cultural traditions that honor human-nature relationships, these approaches create space for acknowledging loss while celebrating continuing connections to place. For indigenous communities in particular, cultural ceremonies that reaffirm relationships with changed environments have proven valuable in addressing collective solastalgia.

Building Resilience in a Changing World

As environmental changes accelerate globally, developing psychological resilience becomes increasingly important. Research suggests that several factors influence how severely individuals experience solastalgia and how effectively they adapt to changed environments. Social cohesion emerges as particularly significant—communities with strong internal bonds typically demonstrate greater collective resilience than those where people face environmental changes in isolation.

Educational approaches that foster environmental literacy may also build psychological resilience. Understanding the scientific aspects of environmental change helps reduce uncertainty and allows individuals to distinguish between temporary changes and permanent transformations. This knowledge doesn’t eliminate grief but can help people contextualize their experiences within broader ecological processes.

Perhaps most importantly, meaningful participation in environmental decision-making appears to buffer against solastalgia’s most severe impacts. When communities have genuine input into development projects, resource management, and climate adaptation efforts, the resulting sense of agency can mitigate feelings of powerlessness. This suggests that addressing solastalgia requires not just psychological interventions but changes to environmental governance that empower affected communities.

As our planet continues to transform, understanding the psychological dimensions of environmental change becomes increasingly crucial. Solastalgia reminds us that our wellbeing remains inextricably linked to the health of our surroundings—and that creating sustainable futures must address both ecological and psychological needs. By acknowledging these connections, we take an important step toward building communities that can navigate environmental changes while maintaining essential bonds to place.